For more than a decade, digital culture has promoted a simple rule: attach your real name and face to your work, and people will trust you. This logic shaped influencer culture, founder branding, and even professional networking. Visibility was framed as authenticity, and authenticity was framed as credibility.

That equation no longer holds. In fact, in an era defined by generative artificial intelligence and deepfakes, the public promotion of one’s image and name has shifted from an asset to a risk. The irony is sharp: the very behaviours once encouraged to signal authenticity now actively undermine it.

Authenticity has not died. What has died is the idea that showing your face is a reliable way to prove it.

The collapse of the face-as-proof model

Historically, faces functioned as trust shortcuts. Humans evolved to read facial cues as indicators of sincerity, intent, and identity. Digital platforms exploited this bias. Research into influencer marketing shows that visible faces, informal aesthetics, and perceived transparency increase audience trust and engagement. Authenticity became something that could be performed visually.

However, generative AI has broken the social contract underpinning that performance. Deepfake technologies now allow faces, voices, and mannerisms to be convincingly replicated with minimal effort and cost. Seeing someone say something is no longer evidence that they ever did.

Legal scholars and policy researchers warned early that deepfakes would destabilise trust infrastructures, not merely spread misinformation. Subsequent studies confirm that synthetic media can alter beliefs, create false memories, and erode confidence in all visual evidence—not just manipulated content. The result is a credibility crisis: if everything can be fake, then nothing visible can be trusted by default.

This is not an abstract problem. Deepfake pornography, harassment campaigns, financial fraud, and political disinformation increasingly rely on readily available public images. The more material that exists of a person online, the easier it becomes to generate plausible fabrications.

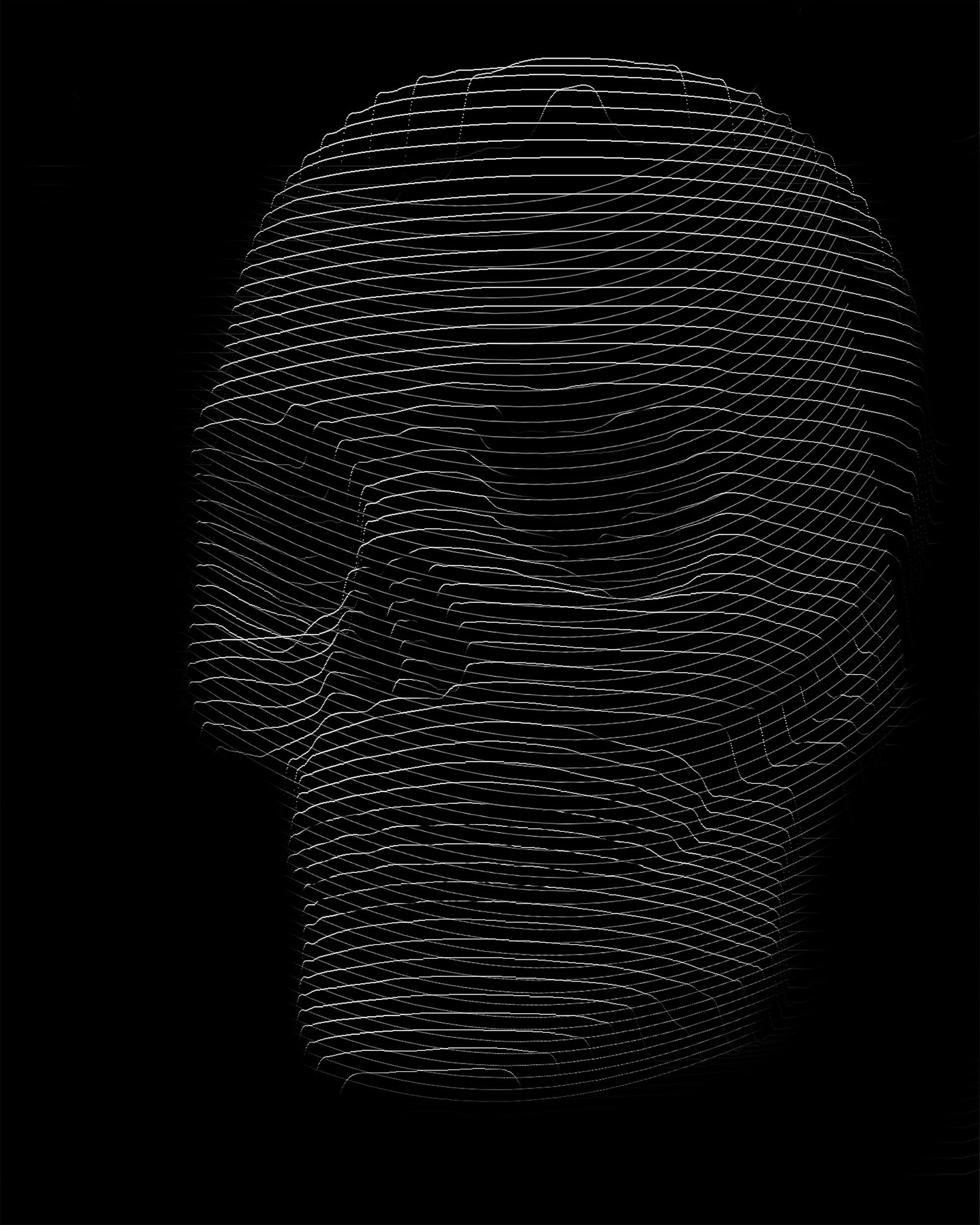

The irreversibility problem of biometric exposure

What many creators and professionals still underestimate is that faces are not just images. They are biometric data.

Unlike passwords, faces cannot be changed. Once sufficient visual data is publicly available, it can be scraped, modelled, and reused indefinitely. Academic research in biometric security consistently highlights this asymmetry: when biometric identifiers are compromised, the damage is permanent.

From this perspective, traditional personal branding advice—post more video, be recognisable, be consistent—reads less like career guidance and more like negligent data exposure. Every additional clip improves the training set for potential misuse.

This is where the argument shifts from aesthetics to ethics. Continuing to promote one’s image as a primary trust signal is not simply outdated; it is dangerous. It assumes a media environment that no longer exists.